WASHINGTON COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY (Washington County, Utah)

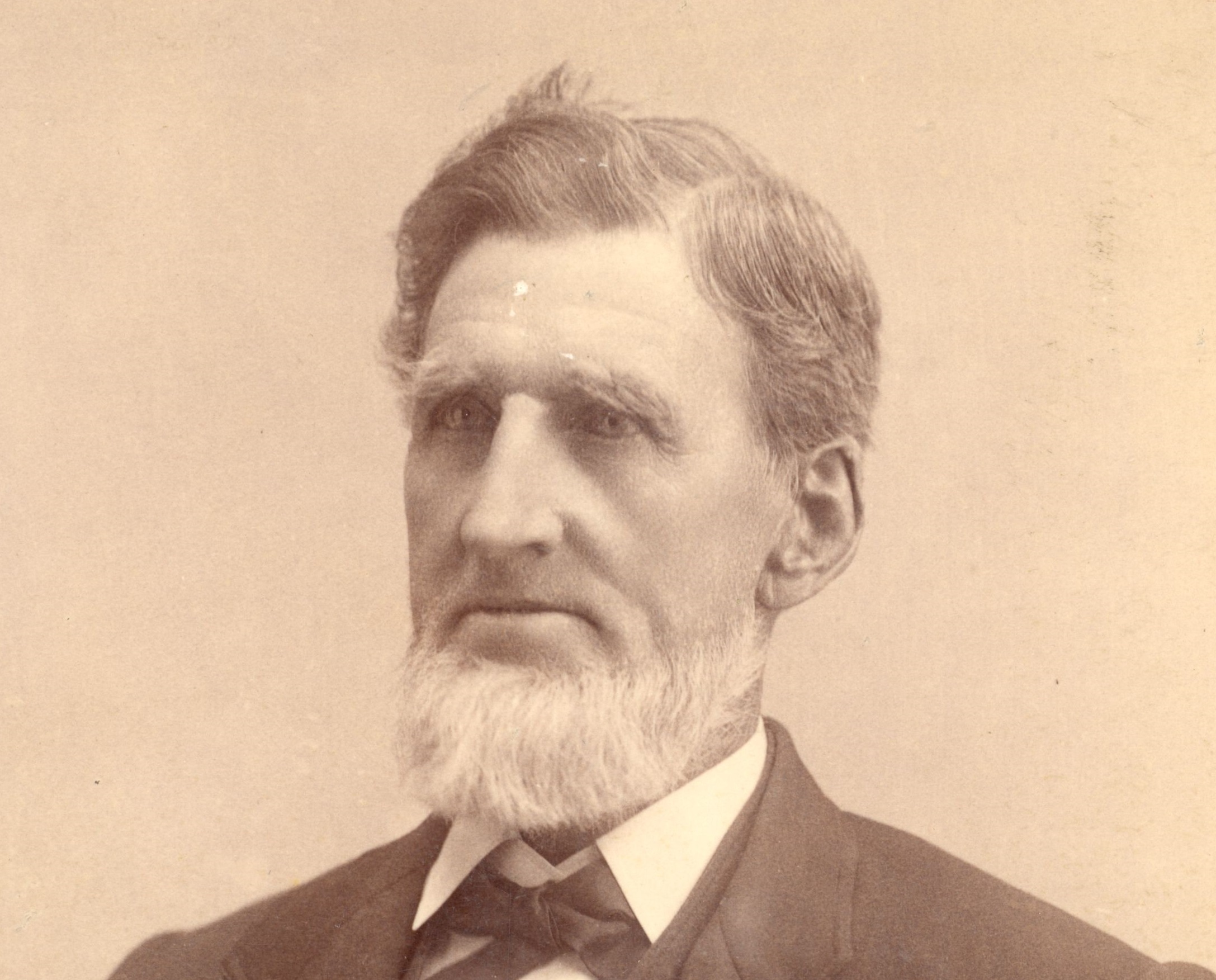

BIOGRAPHY OF ROBERT GARDNER

(from http://library.dixie.edu/info/collections/temple/temple.htm)

When Robert was fourteen, the family moved to Warwick, east of Montreal, on the lower end of Lake Huron. Once again, Robert helped clear land and plant crops. His older brothers having gone off to provide their own livelihood, Robert was the principal support of his aging parents. In 1841, at age twenty-one, he married Jane McKeown, an Irish-Canadian, and Robert and Jane continued to live with his parents.

In 1844, Mormon Elders, preaching in their neighborhood, converted Robert's oldest brother, William, who lived nearby. William, in turn, urged Robert and Jane and his parents to join, which they did in January 1845. Robert, who was now twenty-six, wrote that they went into the woods to a suitable place, cut a hole in the ice which was eighteen inches thick, and William baptized him. Robert wrote, "While under the water, though only about a second, a bright light shone around my head and had a very mild heat with it." Robert was confirmed a few minutes later by Elder Samuel Bolton, as they sat on a log near the water. "I felt like a child," Robert wrote, "and was very careful what I said and did and thought, lest I offend my Father in Heaven."

Once they had embraced the gospel, the Gardners had a strong desire to move to Nauvoo. When they learned that the Saints were leaving Nauvoo for the Rocky Mountains in 1846, all the members of the little Canadian branch left to join their brethren. The Gardners arrived at Nauvoo in April, acquired the supplies for a journey west, then crossed the Mississippi River and headed for Winter Quarters. They joined the company of John Taylor, another Canadian convert, in the 1847 crossing of the Plains, and arrived in the Salt Lake Valley on October 1, 1847. Robert and his brother Archie (Archiblad Gardner) built sawmills on Mill Creek and on the Jordan River and sowed wheat.

Two of Robert Gardner's experiences are worthy of mention. The first occurred during the winter of 1856-57 when he went to the canyon to slide down some timber for firewood; the snow was about five feet deep. Unaware that another party had climbed up the same slide earlier, he was half way up when he was met by a log hurtling down the incline; it struck his right leg below the knee and peeled off a six-inch strip of the calf of his leg, clear to the bone. He felt his leg with his hands and found it was not broken.

Crawling off the path to a high place, he saw two men coining up the canyon and yelled for help. He found the strip of flesh in his boot and tied it to his leg with his handkerchief, hoping it would grow back. He was placed on a wagon and taken to the mill of John Neff, in present day Draper, where he was attended by Porter Rockwell. "Old Port," as he was called, gave him a tumbler of whiskey and molasses. Robert began to put it on his wound, but Porter said to put it inside, "so I dun both." After washing and salting the wound, Port started to sew on the ripped-off flesh with a needle and silk thread, but his heart failed. "So they held me up," Gardner wrote, "and I sewed it myself, and made a good job of it."

His neighbors were all very kind during his recovery and got up "tea parties," as they called them, and he was very grateful. In expressing his thanks, he jokingly blessed the pregnant women of three neighboring homes that they would have twins. He didn't mean it or think any more about it, but shortly all three women had twins-the only twins born that year in the Salt Lake Valley. "Whether my words had anything to do with it or not, they all believed it had. I have been cautious about blessings ever since," he wrote.

In the fall of 1861 his name was among those called to go to southern Utah to make new settlements and raise cotton. Gardner wrote in his diary, "I looked and spat, took off my hat, scratched my head, thought, and said "All right.'" He traded for a span of mules, left his fifteen-year-old son to gather the crops, and started on his mission on November 12. He met George A. Smith at Parowan, who told him to settle in what became St. George and to find suitable places for sawmills. With tongue in cheek, George A. told him and other missionaries that wood was rather scarce, "but by going twelve or fifteen miles to where there was some cedar, by hunting around we might find some sticks long enough for the fireplace by splicing two sticks together." George A. said that "another advantage of the country was that it was a great place for a range. When a cow got one mouthful of grass, she had to range a great way to get another. He said the sheep done pretty well, but they wore their noses off reaching down between the rocks to get the grass. In St. George, water left in the sun got warmed enough to wash dishes in, while thirty miles away the people had to wrap up in bed quilts to keep from freezing."

At Harrisburg, fourteen miles north of St. George, they saw friends who had gone south in 1858 to test the country for growing cotton. "The appearance of these brethren and their wives and children was rather discouraging," Robert wrote. "Nearly all of them had fever and ague. They had worked hard and had worn out their clothes, and had replaced them from the cotton they had raised on their own lots and farms. Their clothes and their faces were all of a color, being blue with chills. This tried me harder than anything I had seen in all my Mormon experience, but I said, 'We will trust in God and go ahead.'"

Robert, his family, and his companions spent that 1861 Christmas Day in St. George by holding a meeting and a dance. They immediately laid out the townsite and began building homes. Robert was superintendent of construction for the St. George Hall. "We were united in everything we did in those days," he wrote. "We had no rich nor poor. Our teams and wagons and what was in them was all we had. We had all things in common in those days, and very common too, especially in the eating line, for we didn't even have sorghum." Robert was chosen as the St. George bishop, and when they organized four wards in 1862, he was sustained as bishop of the Fourth Ward and also of Shoal Creek, Meadows, Pinto, and Pine Valley. He served as bishop until 1869, when he was released to become a counselor in the stake presidency. Upon the death of the stake president, Joseph W. Young, in 1873, he served as acting president in the stake until 1877. He also served as mayor of St. George for two four-year terms.

In 1864 Gardner moved his families to Pine Valley, thirty-two miles away, where he logged and sawed timber for the Tabernacle, other public buildings, and private residences. He also supplied the yellow pine timbers free from knots and resin that went into the beautiful Salt Lake Tabernacle Organ. The lumber for the distinctive and eye-catching frame chapel designed by Ebenezer Bryce in Pine Valley in 1868 was also selected and cut by Robert Gardner.

In the 1860s crops in St. George failed for several seasons. Many suffered from hunger, but Robert's brother Archie and others in northern Utah sent flour and other necessities to sustain them.

In 1876 Brigham Young, now seventy-five years old, suffered from rheumatism and prostate problems, and was anxious to complete the St. George Temple before he died. He had keys which he wanted to give, which could be given only in the temple. Brigham had sent a large steam sawmill to Mount Trumbull, about sixty-five miles southeast of St. George and fifteen miles from the north rim of the Grand Canyon, to provide timber for the Temple and other structures. Workmen at the mill had many problems, and some of them left. Brigham Young was irritated; their failure was holding up work on the Temple. George A. Smith, who was with Brigham, went to Gardner and said that he felt compelled to get someone "who will not be stopped by a trifle, but will get out lumber no matter what it will cost, that the Temple may be finished without delay." Gardner said he would do so if the President insisted. Shortly thereafter he received a telegram asking him to go to Trumbull and "get out that lumber." He went immediately.

Bishop Gardner took men and equipment, arranged for teams and drivers to haul logs to the mill, organized another group at Antelope Springs under Isaac Haight to haul lumber to the Temple for which the masonry work was finished, and soon had a steady stream of lumber running from standing trees to the Temple. After a year he returned to St. George and Pine Valley. He was ordained a patriarch in 1900 and worked as an officiator in the Temple until he died in 1906, age eighty-seven. Before his death he said, "The Dixie country was never much of a country in which to make money, but it is a fine country in which to make men and women."